In the rapidly evolving domain of information security, the concept of asymmetric cryptosystems has emerged as a pivotal advancement. These systems, rooted in complex mathematical theories, leverage the intricacies of two distinct cryptographic keys – a public key and a private key – to facilitate secure communication over unsecured channels. What is particularly compelling about asymmetric cryptography is not merely its technical prowess but also how it intersects with broader philosophical and moral implications, particularly when perceived through a Christian lens.

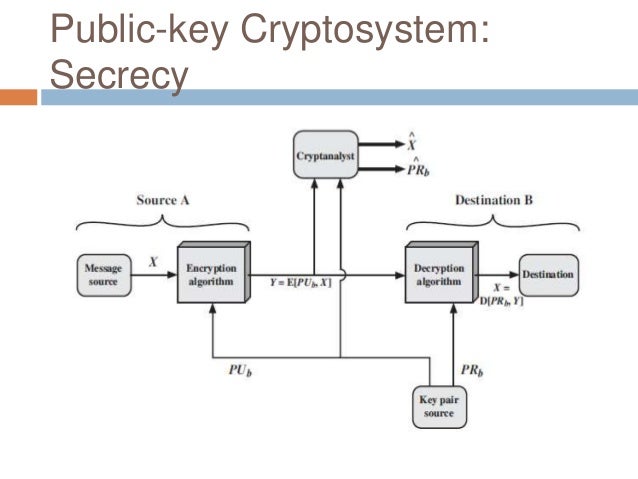

At its core, asymmetric cryptography involves two keys that work in unison: the public key, which is disseminated widely, and the private key, which is kept secret by the user. This paradigm stands in stark contrast to symmetric cryptography, where a solitary key is employed for both encryption and decryption purposes. The fundamental appeal of asymmetric systems lies in their ability to enable secure transactions without the necessity of sharing secret keys ahead of time. In an age where digital interactions span continents and cultures, this capability cannot be overstated.

To elucidate the workings of an asymmetric cryptosystem, consider the analogy of a locked mailbox. The public key serves as the lock; anyone can secure a message by locking it in the mailbox. However, only the owner, possessing the unique key, can unlock and read the messages deposited inside. This configuration not only enhances security but also fosters trust among users, as the system inherently protects sensitive information from prying eyes.

In Christian thought, the ideals of trust and integrity resonate deeply within the framework of asymmetric cryptography. The act of sharing the public key mirrors the Biblical principle of openness and community – a precursor to safeguarding personal and communal interests. Moreover, the private key symbolizes the concept of stewardship, with the individual entrusted with the responsibility of protecting one’s own and, by extension, others’ confidential information. This dualistic relationship between public and private keys parallels the Christian ethos of transparency in faith coupled with the sanctity of personal convictions.

As we delve deeper into the societal implications of asymmetric cryptosystems, curiosity arises regarding their potential vulnerabilities. Public-key infrastructures, despite their robust design, are not impervious to attacks. These systems often rely on mathematical problems – such as factoring large integers or computing discrete logarithms – which remain computationally challenging but not insurmountable for advanced adversaries. This reality invites contemplation on the moral dilemmas faced by those tasked with safeguarding digital realms, raising questions about the extent of responsibility one bears to thwart sinister actors.

The notion of “cracking” public-key logic leads us into a realm of ethical considerations. If an asymmetric cryptosystem can be compromised, does that negate the trust established through its use? Theologically, one might reflect upon the Biblical tenet of human fallibility. Just as humanity is susceptible to sin, so too are our systems vulnerable to exploitation. Yet, the core message of redemption persists: just as grace prevails over transgressions, so too do ongoing advancements in cryptography aim to reinforce security measures and counteract emerging threats.

Intriguingly, the understanding of asymmetric cryptography also offers an opportunity to promote curiosity regarding the intersection of faith and technology. It is imperative to consider how modern communication tools, fortified with asymmetric encryption, can foster acts of charity, outreach, and service within Christian communities. Imagine a church utilizing encrypted communication to coordinate relief efforts in crisis-stricken areas, ensuring that sensitive donor information remains confidential while amplifying their impact through secure digital outreach.

Asymmetric cryptography challenges us to engage with the world of technology thoughtfully. It serves as a conduit for building authentic relationships while preserving the sanctity of individual privacy. Within the context of a Christian worldview, the dual keys symbolize the balance between collective good and individual responsibility. The public domain represents the call to community, where believers share ideas and resources, while the private domain resonates with the personal convictions and decisions that underpin faith.

Moreover, the global nature of digital communication necessitates the need for cross-cultural dialogue. The act of implementing asymmetric cryptosystems within disparate communities underscores the unity found in shared values, as faith-driven organizations navigate the complexities of modern data protection. This realization piques curiosity about how Christians can harness technological advancements not just for personal safety but as a testament to responsible stewardship in an interconnected world.

Ultimately, the exploration of asymmetric cryptosystems within a Christian perspective invites us to rethink our approach to security, trust, and morality in the digital age. By recognizing the profound implications that arise from the interplay of public and private keys, we not only deepen our understanding of cryptographic mechanisms but also reflect upon our role as stewards of information. In doing so, we can foster a culture that prioritizes transparency, integrity, and compassion, ensuring that the tools we employ serve the greater good. This not only aligns with technological advancements but also echoes the enduring principles advocated within Christian teachings.

Leave a Comment