In an age where data privacy and security are paramount, one of the most frequently debated topics is the ability of governments to penetrate advanced encryption standards, notably the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). While AES has been established as one of the most robust encryption technologies available, the dialogue surrounding governmental surveillance casts a long shadow over individual security and privacy. Can the government indeed break AES? To answer this question, we must traverse the intricate landscape of cryptography, legality, and the ethical implications inherent in the tug-of-war between surveillance and security.

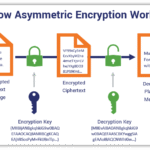

Initially, it is essential to appreciate the architecture of AES. Developed in the late 1990s and adopted by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2001, AES is a symmetric key encryption standard that operates on block sizes of 128 bits with key lengths of 128, 192, or 256 bits. Its strength lies in its complicated mathematical structure, which employs substitution and permutation functions that obfuscate the data significantly. Thus, the sheer number of potential keys (over 340 undecillion for 256-bit AES) creates a virtually insurmountable barrier to brute-force attacks using contemporary computing capabilities.

However, as the proverbial saying goes, “there’s no tool so powerful that man cannot find a way to wield it for nefarious purposes.” The question remains: does this imply that governments possess the resources or technological advancements that could potentially breach AES? To analyze this, we should first consider the two primary facets of this debate: the technological aspect and the ethical implications of potential backdoors.

From a technological perspective, several avenues exist through which decryption could occur. The most obvious route is brute force; however, this method remains a logistical nightmare due to the extensive key space. Nonetheless, advancements in quantum computing present a new paradigm. Quantum computers leverage the principles of quantum mechanics to process information in ways classical computers cannot. Algorithms like Shor’s algorithm, theoretically, could compromise various forms of encryption, including RSA, and pose a future threat to AES as well. Nevertheless, current quantum computers are not yet capable of executing such an attack against AES, as they stand on the precipice of what may be possible.

Besides the brute force and quantum computing avenues, vulnerabilities could also originate from implementation flaws or side-channel attacks. If a system employing AES is poorly implemented or contains vulnerabilities, an attacker, possibly even a government entity, may exploit those weaknesses without needing to break the encryption itself. This consideration highlights the importance of not only the strength of the algorithm but also the significance of its application in real-world scenarios.

The notion of government-mandated backdoors complicates this discussion profoundly. Proponents argue that such measures would allow law enforcement and national security agencies to access encrypted communications in a bid to thwart criminal activity or terrorism. At first glance, this justification seems reasonable, akin to a key that permits entry into a locked building in emergencies. However, the peril lies in trust. As history has shown, once a vulnerability is established, the potential for misuse increases exponentially. A backdoor that is ostensibly designed for good could easily become a tool for tyranny, compromising the privacy rights of individuals.

Moreover, the philosophical implications of governmental surveillance warrant scrutiny. When governments engage in mass surveillance, they create a society under constant observation—a condition reminiscent of George Orwell’s dystopia in “1984.” In this scenario, the right to privacy erodes, leading to self-censorship and stifled free expression. A balance must be struck: while security from threats is paramount, the sacrifice of individual liberties is a price too steep to pay.

Furthermore, the legal frameworks surrounding encryption and surveillance add additional layers of complexity to this issue. Laws differ from one jurisdiction to another, and the efficacy of these regulations in safeguarding personal privacy remains ambiguous. A push for legislation that favors transparency over ambiguity in surveillance practices could serve to protect both security interests and civil liberties. Comparably, it is crucial to advocate for a framework where governments remain accountable for their surveillance practices.

In conclusion, while the government may not currently possess the technological prowess to break AES outright, the fluidity of advancements in computing and cyber capabilities introduces uncertainties that linger on the horizon. This dilemma encapsulates the broader struggle between surveillance and security. As we navigate this contentious terrain, it is imperative to champion a future where technological innovation is harnessed in a manner that fortifies our freedoms rather than compromises them. The challenge lies in fostering an environment of trust and transparency while mitigating the power imbalance entrenched in the current surveillance landscape.

The pursuit of security may not always align with the protection of personal liberties. The duality of these interests demands continual dialogue, ensuring that as society evolves, the balance between security and personal freedom remains equitable. The implications of the AES conundrum extend far beyond mere technicality; they reverberate throughout the fabric of democracy itself.

Leave a Comment