In a world increasingly dominated by electronic communication, the pursuit of secure information exchange has never been more urgent. Among the myriad cryptographic techniques that have emerged over the centuries, one stands out for its elegance and purported invincibility: the Vernam cipher. This cipher, heralded as the unbreakable classic of cryptography, invites both admiration and scrutiny. The apparent strength of the Vernam cipher raises a tantalizing question: can we, as rational beings, trust the security promised by this methodology in our modern context?

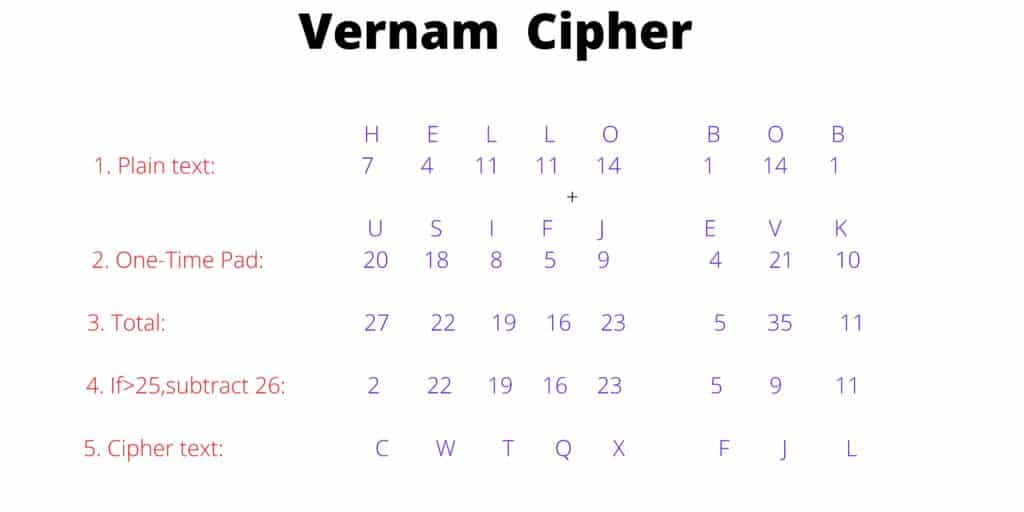

The Vernam cipher, conceived in 1917 by the American engineer Gilbert Vernam, utilizes a unique keying system against a plaintext message. Unlike traditional ciphers that often rely on fixed keys or algorithms, the key in this case is as long as the message itself and is random. The fundamental operation is remarkably simple: each character of the plaintext is combined with the corresponding character of the key through the logical exclusive OR (XOR) operation. The result is an encrypted message that is incomprehensible without the key.

Imagine a scenario: two individuals, Alice and Bob, wish to pass along sensitive information without interception. They share a key that is as long, unpredictable, and ephemeral as their message. The resultant encryption process yields a ciphertext so robust that without the key, deciphering the content becomes a Sisyphean task, regardless of computational prowess.

This leads to a pivotal characteristic of the Vernam cipher: its perfect secrecy. The concept of perfect secrecy, pioneered by Claude Shannon, implies that when the cipher is executed under certain conditions, an adversary, even with unlimited computational resources, cannot deduce the plaintext. This magical allure positions the Vernam cipher as the Holy Grail of classical cryptographic methods.

Nevertheless, perfection is predicated on specific criteria. The key must be truly random, at least as lengthy as the plaintext, shared securely, and never reused. Each of these stipulations presents formidable challenges in practical applications. The randomness of the key is paramount; any repeat patterns can result in vulnerabilities that potential adversaries might exploit. The sharing of such a key without interception, particularly over insecure channels, is fraught with complications. Furthermore, reusing keys, a common failing in cryptography, negates the promised security, transforming the cipher from an impenetrable fortress into a mere paper wall.

But why delve deeply into the intricacies of the Vernam cipher? The answer lies not merely in cryptographic theory but in the broader implications within a Christian perspective. Do we not, as believers, strive for transparency and authenticity in our dealings? The challenge presented by the Vernam cipher beckons us to consider the balance between security and openness, trust and isolation. In a world where information is currency, how can we ethically navigate the waters of secrecy?

The analogy of the Vernam cipher extends beyond algorithms and computations; it resonates with the human experience. Just as the key serves to validate the communication process, faith functions as a divine key in our interpersonal engagements. It serves as the binding element that unlocks personal connections, fostering an environment of trust and understanding. The potential misuse of this divine key—sharing confidences inappropriately or withholding it from those who need it most—is akin to utilizing a reused key in the Vernam cipher; it undermines the very premise of security and integrity.

Moreover, the challenge of maintaining security in the Vernam cipher can be likened to the trials of Christian discipleship. The commitment to uphold one’s principles in a world rife with temptation mirrors the diligence required to preserve the integrity of the cipher. It calls into question the lengths to which one is willing to go to safeguard their values—much like the fastidious care one must take in managing the keys of encryption.

In our reflections, we must also confront the transient nature of earthly securities. The intricacies inherent in the Vernam cipher serve as a reminder that complete invulnerability is an illusion. Just as keys must be renewed and updated in cryptographic practice, so too must our commitments to faith and community evolve. The passage of time, intertwined with human fallibility, suggests that security—be it in the form of cryptographic keys or relationships—requires persistent nurturing and vigilance.

In conclusion, while the Vernam cipher presents a formidable challenge to those who would seek to undermine it, its principles extend far beyond the realm of cryptography. It urges us to ponder the philosophies of trust, integrity, and accountability in both personal and communal settings. As we embrace the complexities of life and the intricasies of our existence, let us remember that encryption is not solely about safeguarding messages. Rather, it encapsulates our moral endeavors to reconcile security with transparency, all while anchoring ourselves in faith’s unwavering promise of hope and connection.

Leave a Comment