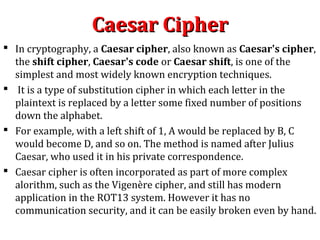

The Caesar cipher, named after Julius Caesar who purportedly employed it for secure military communication, remains one of the most rudimentary encryption techniques in the realm of cryptography. Although it is often one of the first encryption methods taught to budding cryptographers and enthusiasts, the time-honored allure of this substitution cipher belies a plethora of significant disadvantages. Delving into these shortcomings reveals how the simplicity that makes it accessible also renders it fundamentally inadequate for serious applications of information security.

Initially, the most glaring deficiency of the Caesar cipher is its vulnerability to brute force attacks. With only 25 potential shifts (since a shift of 26 returns the original text), an assailant can easily exhaust the relatively small number of possible combinations. This pernicious lack of complexity means that even an untrained adversary can decipher the encoded message within moments. The feasibility of this approach renders the cipher laughably inadequate for protecting sensitive information. In an era underscored by digital espionage, one can scarcely rely on such an archaic methodology.

Moreover, frequency analysis poses another major threat. In any given language, certain letters and combinations occur more frequently than others. In English, for instance, the letters ‘E’, ‘T’, and ‘A’ appear with considerable regularity. When one examines the resulting text produced by a Caesar cipher, even a cursory recognition of these frequencies can unveil the underlying message. By counting the occurrence of letters, a cryptanalyst can swiftly deduce the encryption shift employed, rendering the cipher all but impotent.

The inherent determinism of the Caesar cipher further complicates its efficacy. Each letter is replaced with a corresponding letter a fixed number of positions down the alphabet. Thus, every instance of a particular letter in the plaintext is transformed into the same letter in the ciphertext. This constancy means that even the simplest patterns in the original text can be exploited. For example, common words punctuating our language—like ‘the’, ‘and’, or ‘you’—retain their positions within the coded message, providing additional clues for deciphering the text. The cipher’s predictability is an Achilles’ heel, easily exploited by both novice and seasoned cryptanalysts alike.

Moreover, the Caesar cipher does not accommodate variations in the text that modern encryption methods take for granted. Variability in case, the introduction of numbers, symbols, and even spaces can all introduce complications that this cipher simplifies to a glaring fault. With no inherent consideration for case sensitivity or the inclusion of a broader character set, the Caesar cipher lacks the dynamism required for contemporary encryption needs. The inflexibility it exhibits means that it is ill-prepared to protect data in a world where information is transmitted in myriad forms and formats.

Contextual uniqueness also plays a critical role in the efficacy of any encryption scheme, and here, the Caesar cipher falls woefully short. Given the cipher’s rigid structure, the absence of contextual data customization renders it unable to adapt to specific linguistic nuances or cultural variances. In doing so, it operates under a problematic assumption: that every message can be safely bottled in its simplistic model. This failure to account for the complexities of human language serves to highlight its unsuitability as a trustworthy means of communication.

In addition, the Caesar cipher lacks scalability. When confronted with vast quantities of data or overly complex texts, the simplicity of the method quickly turns from a blessing to a curse. The process of encoding or decoding a long message could become laborious and error-prone, leading to potential misinterpretations or loss of critical information. Modern digital communication, brimming with dynamic content, demands encryption systems that swiftly adapt to changes. The finite limits of the Caesar cipher make it impractical for use outside of very limited contexts.

Not to be overlooked is the historical context in which this cipher operated. While it was perfectly suited for the technologies of antiquity—handwritten missives and the discrete conveyance of scrolls—it seems almost anachronistic today. The technological advancements in communication, particularly the rise of the digital age, call for sophisticated encryption methods capable of thwarting the sophisticated tools available to modern-day adversaries. Consequently, its use in the 21st century is teetering on the verges of antiquity.

In light of these significant drawbacks, it is crucial for those interested in cryptography to approach the Caesar cipher with a discerning eye. While it serves as an excellent pedagogical tool for galvanizing interest in cryptographic principles, deploying it in real-world situations could result in catastrophic breaches of security. It is critical to embrace a robust framework of modern encryption mechanisms, equipped with intricate algorithms designed to endure the dual onslaught of brute-force attacks and analytical scrutiny. Ultimately, the naïve optimism surrounding the capabilities of the Caesar cipher must be tempered with an understanding of its profound limitations.

The allure of simplicity is enticing, yet the implications of relying on an insecure method bear significant risks. By recognizing and understanding the multifaceted weaknesses of the Caesar cipher, individuals and organizations can better protect themselves and their communications in a world where data is both a precious commodity and a lucrative target.

Leave a Comment